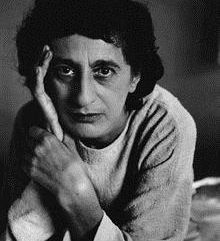

Anni Albers

1899 - 1994

Anni Albers was a German-Jewish visual artist and printmaker. A leading textile artist of the 20th century, she is credited with blurring the lines between traditional craft and art. Born in Berlin in 1899, Fleischmann initially studied under impressionist painter Martin Brandenburg from 1916 to 1919 and briefly attended the Kunstgewerbeschule in Hamburg in 1919. She later enrolled at the Bauhaus, an avant-garde art and architecture school founded by Walter Gropius in Weimar in 1922, where she began exploring weaving after facing restrictions in other disciplines due to gender biases at the institution.

Under the guidance of Gunta Stölzl, Fleischmann developed a passion for the tactile qualities of weaving, shifting her artistic focus from painting to textile art. In 1926, Fleischmann married fellow Bauhaus figure Josef Albers, taking on her husband's last name, and moved with the school to Dessau. The Bauhaus's emphasis on functional design led to innovations in materials that combined aesthetics with practical benefits like sound absorption and light reflection. She eventually headed the weaving workshop after Gunta Stölzl's departure in 1931. The political pressures of Nazi Germany forced the Albers to relocate to the United States in 1933, where Anni Albers took up a teaching position at Black Mountain College in North Carolina.

In 1949, Albers became the first textile designer to have a solo exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. After leaving Black Mountain College, she continued to create textile designs and ventured into printmaking. In the subsequent years, the Josef and Anni Albers Foundation was founded to "perpetuate the vision of Anni and Josef Albers through exhibitions, publications, education, and outreach concomitant with the Alberses' personal values".

Career

In 1925, Fleischmann married Josef Albers, the latter having rapidly become a "Junior Master" at the Bauhaus. The school moved to Dessau in 1926, and a new focus on production rather than craft at the Bauhaus prompted Anni Albers to develop many functionally unique textiles combining properties of light reflection, sound absorption, durability, and minimized wrinkling and warping tendencies. She had several of her designs published and received contracts for wall hangings.

For a time, Albers was a student of Paul Klee, and after Walter Gropius left Dessau in 1928 the Alberses moved into the teaching quarters next to both the Klees and the Kandinskys. During this time, the Alberses began their lifelong habit of traveling extensively: first through Italy, Spain, and the Canary Islands. In 1930, Albers received her Bauhaus diploma for innovative work: her use of a new material, cellophane, to design a sound-absorbing and light-reflecting wallcovering.

When Gunta Stölzl left the Bauhaus in 1931, Albers took over her role as head of the weaving workshop, making her one of the few women to hold such a senior role at the school.

Besides surface qualities, such as rough and smooth, dull and shiny, hard and soft, textiles also includes colour, and, as the dominating element, texture, which is the result of the construction of weaves. Like any craft it may end in producing useful objects, or it may rise to the level of art.

The Bauhaus at Dessau was closed in 1932 under pressure from the Nazi party and moved briefly to Berlin, permanently closing a year later in August 1933. Albers, who was Jewish, made the move with her husband and the Bauhaus to Berlin, but then fled to North Carolina, where the couple was invited by Philip Johnson to teach at the experimental Black Mountain College, arriving stateside in November 1933. Albers served as an assistant professor of art. The school was focused on "learning by doing" or "hands-on learning." In the early 1940s when Albers moved classrooms and the looms were not yet set up, she had her students go outside and find their own weaving materials. This was a basic exercise on material and structure. Albers regularly experimented with different material in her work and this allowed the students to imagine what it might have been like for the ancient weavers. Anni and Josef Albers both taught at Black Mountain until 1949. During these years Albers's design work, including weavings, were shown throughout the US. She received her US citizenship in 1937. In 1940 and 1941, Albers co-curated a traveling exhibition on jewellery from household with one of the Black Mountain students, Alex Reed, that opened in the Willard Gallery in New York City.

In 1949, Albers became the first textile designer to have a solo exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City. Albers's design exhibition at MoMA began in the fall and then toured the US from 1951 until 1953, establishing her as one of the most important designers of the day. During these years, she also made many trips to Mexico and throughout the Americas, becoming an avid collector of pre-Columbian artwork.

After leaving Black Mountain in 1949, Albers moved with her husband to Connecticut where she set up a studio in her home. After being commissioned by Gropius to design a variety of bedspreads and other textiles for Harvard University, and following the MoMA exhibition, Albers was approached by Florence Knoll to design textiles for the Knoll furniture company. For the next thirty years she worked on mass-producible fabric patterns, creating the majority of her "pictorial" weavings, some of which are still in production over fifty years later. She also published a half-dozen articles and a collection of her writings, On Designing. In 1961, she was awarded the Craftmanship Medal by the American Institute of Architects.

In 1963, while at the Tamarind Lithography Workshop in Los Angeles with her husband for a lecture of his, Albers was invited to experiment with print media. She immediately grew fond of the technique, and thereafter gave up most of her time to lithography and screen printing. She was invited back as a fellow to Tamarind in 1964. Here she created the six print portfolio titled, Line Involvements. Albers wrote an article for the Encyclopædia Britannica in 1963, and then expanded on it for her second book, On Weaving, published in 1965. The book was a powerful statement of the midcentury textile design movement in the United States. Her design work and writings on design helped establish Design History as a serious area of academic study.

In 1976, Albers had two major exhibitions in Germany, and a handful of exhibitions of her design work, over the next two decades, receiving a half-dozen honorary doctorates and lifetime achievement awards during this time as well, including the second American Craft Council Gold Medal for "uncompromising excellence" in 1981. In 2018, the Tate Modern Gallery in London paired with the Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen, in Düsseldorf (Germany) for a retrospective exhibition and book of Albers's work.

Albers continued to travel to Latin America and Europe, to design and make prints, and lecture until her death on May 9, 1994, in Orange, Connecticut. Josef Albers, who had served as the chair of the design department at Yale University after the couple had moved from Black Mountain to Connecticut in 1949, predeceased her in 1976.

Text courtesy of Wikipedia, 2024