Joseph Kosuth

1945 - Present

Joseph Kosuth is an American conceptual artist, who lives in New York and Venice, after having resided in various cities in Europe, including London, Ghent and Rome.

Work

Kosuth belongs to a broadly international generation of conceptual artists that began to emerge in the mid-1960s, stripping art of personal emotion, reducing it to nearly pure information or idea and greatly playing down the art object. Along with Lawrence Weiner, On Kawara, Hanne Darboven and others, Kosuth gives special prominence to language. His art generally strives to explore the nature of art rather than producing what is traditionally called "art". Kosuth's works are frequently self-referential. He remarked in 1969:

Kosuth's works frequently reference Sigmund Freud's psycho-analysis and Ludwig Wittgenstein's philosophy of language.

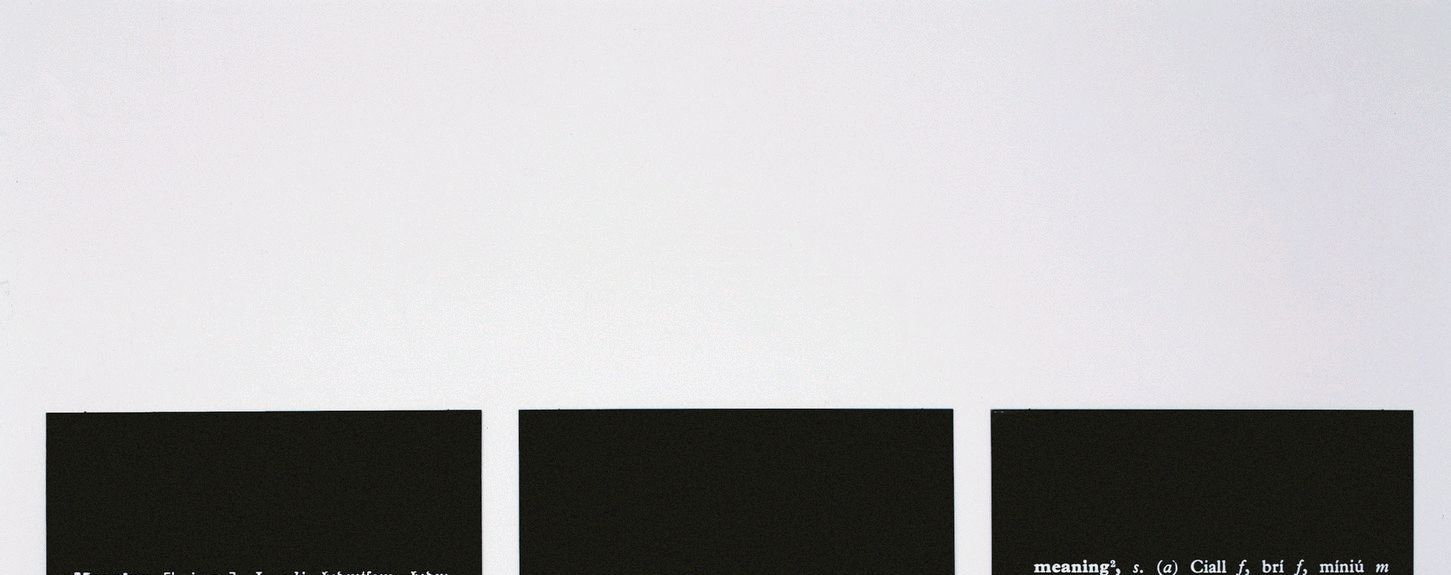

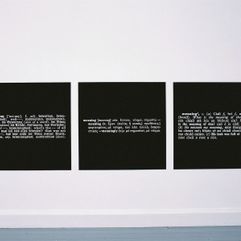

His first conceptual work Leaning Glass, consisted of an object, a photograph of it and dictionary definitions of the words denoting it. In 1966 Kosuth also embarked upon a series of works entitled Art as Idea as Idea, involving texts, through which he probed the condition of art. The works in this series took the form of photostat reproductions of dictionary definitions of words such as "water", "meaning", and "idea". Accompanying these photographic images are certificates of documentation and ownership (not for display) indicating that the works can be made and remade for exhibition purposes.

One of his most famous works is One and Three Chairs. The piece features a physical chair, a photograph of that chair, and the text of a dictionary definition of the word "chair". The photograph is a representation of the actual chair situated on the floor, in the foreground of the work. The definition, posted on the same wall as the photograph, delineates in words the concept of what a chair is, in its various incarnations. In this and other, similar works, Four Colors Four Words and Glass One and Three, Kosuth forwards tautological statements, where the works literally are what they say they are. A collaboration with independent filmmaker Marion Cajori, Sept. 11, 1972 was a Minimalist portrait of sunlight in Cajori's studio.

His seminal text Art after Philosophy, written in 1968-69, had a major impact on the thinking about art at the time and has been seen since as a kind of "manifesto" of Conceptual art insofar as it provided the only theoretical framework for the practice at the time. (As a result, it has since been translated into 14 languages, and included in a score of anthologies.) It was, for the twenty-four year old Kosuth that wrote it, in fact more of a "agitprop" attack on Greenbergian formalism, what Kosuth saw as the last bastion of late, institutionalized modernism more than anything else. It also for him concluded at the time what he had learned from Wittgenstein - dosed with Walter Benjamin among others - as applied to that very transitional moment in art.

In the early 1970s, concerned with his "ethnocentricity as a white, male artist", Kosuth enrolled in the New School to study anthropology. He visited the Trobriand Islands in the South Pacific (made famous in studies by the anthropologist Bronislaw Malinowski), and the Huallaga Indians in the Peruvian Amazon.

For Kosuth, his studies in cultural anthropology were a logical outgrowth that followed from his interest in the "anthropological" dimension of the later Wittgenstein. Indeed, it was the later Wittgenstein of the Investigation - which by accident he had read first - that led to works such as One and Three Chairs (among other influences), not the Tractatus as is often assumed. His anthropological "field work" was organized by him only for the purpose of informing his practice as an artist. (As he said to friends at the time: "some artists learn how to weld, others go back to school.") By the early 1970s, he had an internationally recognized career and was in his late 20s. He found that he was, as he put it, "a Eurocentric, white, male artist", and was increasingly culturally and politically uncomfortable with all that seemed naturally acceptable to his location. His study of cultural anthropology (and it was the New School perspective of Vico, Rousseau, Marx that provided him a direction out of the Ango-American philosophical context) led him to decide to spend time within other cultures, deeply embedded in other world views. He spent time in the Peruvian Amazon with the Yagua Indians living deep into the Peruvian side of the Amazon basin. He also lived in an area of Australia some hundreds of kilometers north of Alice Springs with an Aboriginal tribe that, before they were re-located four years previously from an area farther north, had not known of the existence of white people. Later, he spent time in the Trobriand islands with the Aboriginal tribe that Malinowski had studied and wrote on. From Kosuth's point of view, "I knew I could, would, never enter into their cultural reality, but I wanted to experience the edge of my own." It was this experience and study which lead to his well-known text The Artist as Anthropologist in 1975.

Hung on walls, his signature dark gray, Kosuth's later, large photomontages trace a kind of artistic and intellectual autobiography. Each consists of a photograph of one of the artist's own older works or installations, overlaid in top and bottom corners by two passages of philosophical prose quoted from intellectuals identified only by initials (they include Jacques Derrida, Martin Buber and Julia Kristeva).

Collaborations

In 1992, Kosuth designed the album cover for Fragments of a Rainy Season by John Cale.

Two years later, Kosuth collaborated with Ilya Kabakov to produce The Corridor of Two Banalities, shown at the Centre for Contemporary Art in Warsaw. This installation included 120 tables in a row to present text somewhat symptomatic of the cultures of which they both came from.

Commissions

Since 1990 Kosuth has also begun working on various permanent public commissions. In the early 1990s, he designed a Government-sponsored monument to the Egyptologist Jean Francois Champollion who deciphered the Rosetta Stone in Figeac; in Japan, he took on the curatorship of a show celebrating the Tokyo opening of Barneys New York; and in Frankfurt, Germany, and in Columbus, Ohio, he conceived neon monuments to the German cultural historian Walter Benjamin. In 1994, for the city of Tachikawa, Kosuth designed Words of a Spell, for Noëma, a 136-foot-long mural composed of quotes from Michiko Ishimure and James Joyce.

After projects at public buildings such as the Deutsche Bundesbank (1997), the Parliament House, Stockholm (1998), and the Parliament of the Brussels-Capital Region (1999), Kosuth was commissioned to propose a work for the newly renovated Bundestag in 2001, he designed a floor installation with texts by Ricarda Huch and Thomas Mann for the Paul Löbe Haus. In 2003, he created three installations in the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston, employing text, archival material, and objects from the museum's collection to comment on the politics and philosophy behind museum collections. In 2009, Kosuth's exhibition entitled ni apparence ni illusion (Neither Appearance Nor Illusion), an installation work throughout the 12th century walls of the Louvre Palace, opened at the Musée du Louvre in Paris and became a permanent work in October 2012. In 2011, celebrating the work of Charles Darwin, Kosuth created a commission in the library where Darwin was inspired to pursue his evolutionary theory. His work on the façade of the Council of State of the Netherlands will be inaugurated in October 2011 and he is currently working on a permanent work for the four towers of the façade of the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris, expected to be completed in 2012.

Lecturer

Kosuth has taught widely, as a guest lecturer and as a member of faculties at the School of Visual Arts, New York City (1967-85); Hochschule für bildende Künste Hamburg (1988-90); State Academy of Fine Arts Stuttgart (1991-97); and the Academy of Fine Arts, Munich (2001-06). Currently Professor at Istituto Universitario di Architettura, Venice, Kosuth has functioned as visiting professor and guest lecturer at various universities and institutions for nearly forty years, some of which include: Yale University; Cornell University: New York University; Duke University; UCLA; Cal Arts; Cooper Union; Pratt Institute; The Museum of Modern Art, New York, Art Institute of Chicago, Royal Academy, Copenhagen; Ashmolean Museum, Oxford University; University of Rome, Berlin Kunstakademie; Royal College of Art, London; Glasgow School of Art; Hayward Gallery, London; Sorbonne, Paris; and the Sigmund Freud Museum, Vienna. His students have included, among others, Michel Majerus.

Writings

Kosuth became the American editor of the Art & Language journal in 1969. He later was coeditor of The Fox magazine in 1975-76 and art editor of Marxist Perspectives in 1977-78. In addition, he has written several books on the nature of art and artists, including Artist as Anthropologist. In his essay "Art after Philosophy" (1969), he argued that art is the continuation of philosophy, which he saw at an end. He was unable to define art in so far as such a definition would destroy his private self-referential definition of art. Like the Situationists, he rejected formalism as an exercise in aesthetics, with its function to be aesthetic. Formalism, he said, limits the possibilities for art with minimal creative effort put forth by the formalist. Further, since concept is overlooked by the formalist, "Formalist criticism is no more than an analysis of the physical attributes of particular objects which happen to exist in a morphological context". He further argues that the "change from 'appearance' to 'conception' (which begins with Duchamp's first unassisted readymade) was the beginning of 'modern art' and the beginning of 'conceptual art'." Kosuth explains that works of conceptual art are analytic propositions. They are linguistic in character because they express definitions of art. This makes them tautological. Art After Philosophy and After Collected Writings, 1966-1990 reveals between the lines a definition of "art" of which Joseph Kosuth meant to assure us. "Art is an analytical proposition of context, thought, and what we do that is intentionally designated by the artist by making the implicit nature of culture, of what happens to us, explicit - internalizing its 'explicitness' (making it again, 'implicit') and so on, for the purpose of understanding that is continually interacting and socio-historically located. These words, like actual works of art, are little more than historical curiosities, but the concept becomes a machine that makes the art beneficial, modest, rustic, contiguous, and humble."

Text courtesy of Wikipedia, 2024